A Hacker's Guide for Surviving Volatile Careers Financially

This is a strange post for a blog focused on computers and hacking, but I work in startups, and they are known to fail unexpectedly. Generic advice is not helpful, and paid advisors often have no idea about startup funding cycles or the problems that areise when your income is in a different currency then living expenses -- I had to pay $120 for that lesson. This has forced me to examine my own finances and ensure I will be okay even if my job disappears tomorrow and I have no income for a year or more. It turns out personal finance is a fun optimization problem to solve. I want to share what I have learned, and my time will be well spent if this post helps even one reader.

Of course, I am not a financial advisor and have no certification to give financial advice. I am only sharing my personal experience and what I learned. One thing I will not cover is tax. I do not hold US citizenship, so I pay no tax to the IRS. The tax law in Taiwan means foreign investment is tax free until I am wealthy enough that it becomes an issue (> approx USD $250k in pure profits and forign income per year). I am also not going to recommend what to buy. That is a question you need to answer for yourself.

For context, I am familiar with Taiwan's banking system and US brokerages. This setup makes sense to me because of the laws, taxes, and where I happen to live. Your situation will likely be different. Think from first principles. This post only shows what makes sense to me personally. I have already solved personal finance 101:

- No high interest debt (credit card debt, payday loans, etc.)

- Live below my means

- Save and invest by default

And some critical things I have setup already:

- No long term debt obligations (mortgages, student loans, etc.)

- I DO NOT have the country's labor insurance (foreign income) for unemployment benefits

- Taiwan NHI still applies and I have additional, cheap health insurance

The problem is not whether or why invest. The question is how to structure my investments to serve me best. I am an atypical case where generic advice is actually harmful.

Figuring it out is not an easy process. Look months to figure out what I actually want, what does financial institutions offer, what discounts at banks peovide that changes the math and what's impossible.

Goal setting

Finance is mostly about tradeoffs. Everything you own, whether cash or stocks, has different properties. Some tend to increase in value over time but might dip in between, some pay a predictable amount of cash per year, and some might lose money by default with a chance of making a lot. Before you can evaluate which tradeoffs make sense, you need to decide what you want to achieve. Tradeoffs themselves are not inherently bad. Someone might say, "You should always save 10% of your income." For what purpose? If I am spending 100% of my income just to survive on discounted white bread and the cheapest rent I can find, saving 10% is pointless compared to the goal of surviving. Most people have a different set of goals. Most people want to:

- Retire at the age of 65

- Pay off all debt

- Buy a house

- Buy a car

- Support or have children

My goals are different. I want to:

- Have fun working with computers

- Survive for a long time even with zero income if I lose my job

- I do not plan on retiring, but I suppose I will reach an age when I can no longer work or my work becomes obsolete

- Do interesting and socially helpful work instead of just making money

As you can see, my goals are different from the average person. That means I have a different set of tradeoffs to consider. Everyone has their own set of goals, whether it is paying off debt in the short term or retiring early in the long term.

Also, understand that there are two types of risk that often get mixed together when people talk about finance:

- Price volatility (the number your broker or bank shows you owning goes down)

- Shortfall risk (you fail to achieve your stated goal or end up poor due to bad luck)

The obvious and simple solution is to calculate how much money you need and keep that amount in your bank account. That actually works. BUT inflation usually runs at least 2% while banks pay you almost nothing on your deposit. You can do much better than that. By doing so, interestingly, your goals become easier to reach. Savings are "liquid." You can withdraw from savings at any time to pay your bills. They are also principal protected, so you cannot lose your money. You can exchange either (or both) liquidity or principal protection for higher returns. For example, most banks offer Certificates of Deposit (CDs), which say, "You will not be allowed to touch your money for X months, and in return, we pay you twice as much interest compared to a savings account. We still guarantee you will get your money back." This is where things get interesting and where investing comes into play.

Instruments

We need to talk about instruments before investing. Instruments are the things you buy (and sell) to make money. They are the building blocks of investing. The totality of what you own is your portfolio. There are far too many instruments to cover in this post, so I will mention some important ones you might consider, depending on your own goals.

Most people reading this blog are probably engineers rather than economics majors, so here is a refresher.

Cash

I count cash as an instrument. Here, I am using the concept of cash very generally. Cash is what you use to buy things and pay taxes. It could be paper cash in your wallet or the number in your bank account. There are different types of cash. The United States uses USD. Europe generally uses EUR. For me, living in Taiwan, that is TWD. Cash has zero (paper cash) to very little (in your account) interest. But it is the only thing you can use to buy coffee.

If you have ever read about economics, this is M1. If you do not understand, do not worry about it.

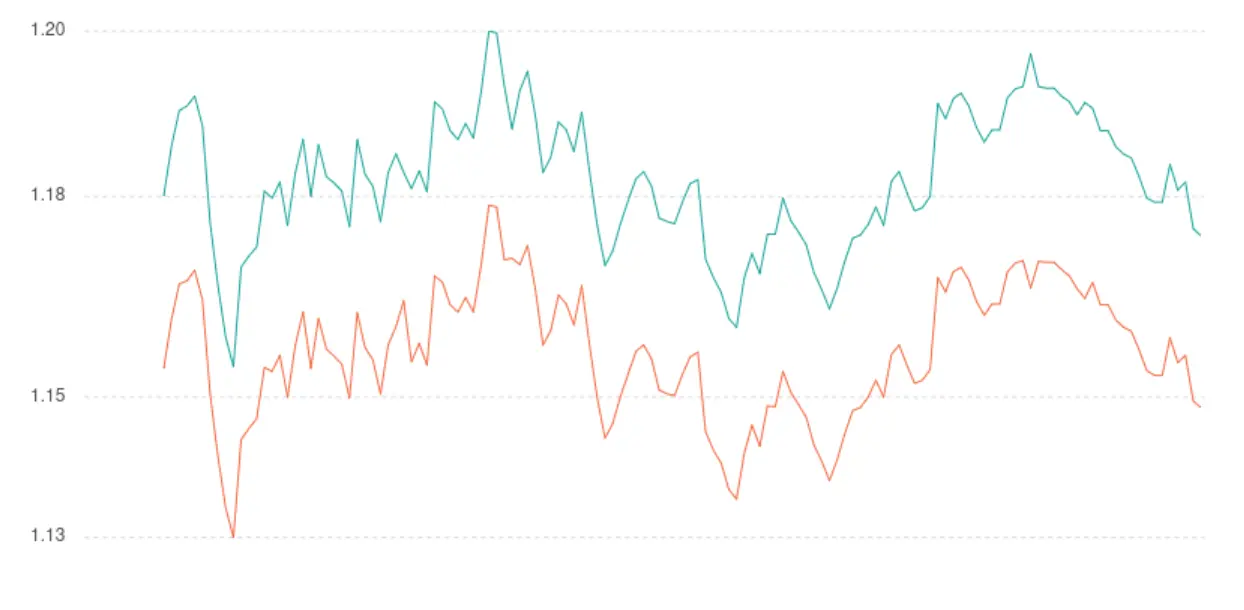

The type of cash is called currency. Banks usually allow exchange between different currencies, for a fee. For example, you live in the US and earn USD, but you plan to vacation in Europe where you need EUR. You can exchange your USD for EUR at the bank. The conversion rate between USD and EUR is called the exchange rate, and the act is called foreign exchange (FX). In most cases, the exchange rate from USD to EUR and EUR to USD is not the inverse of each other. Banks make money this way. You get slightly less each time you exchange. This is called the spread.

Certificates of Deposit (CDs)

As described above, you can exchange the liquidity of your cash for higher returns. Banks provides this by offering Certificates of Deposit (CDs). With CDs, you give the bank some money and tell them how long you want them to keep it. In return, they pay you a higher interest rate. That rate depends on both the length of the CD and the current interest rate set by the government. Usually, the longer the CD, the higher the interest rate, but that is not guaranteed. It depends on what the bank offers.

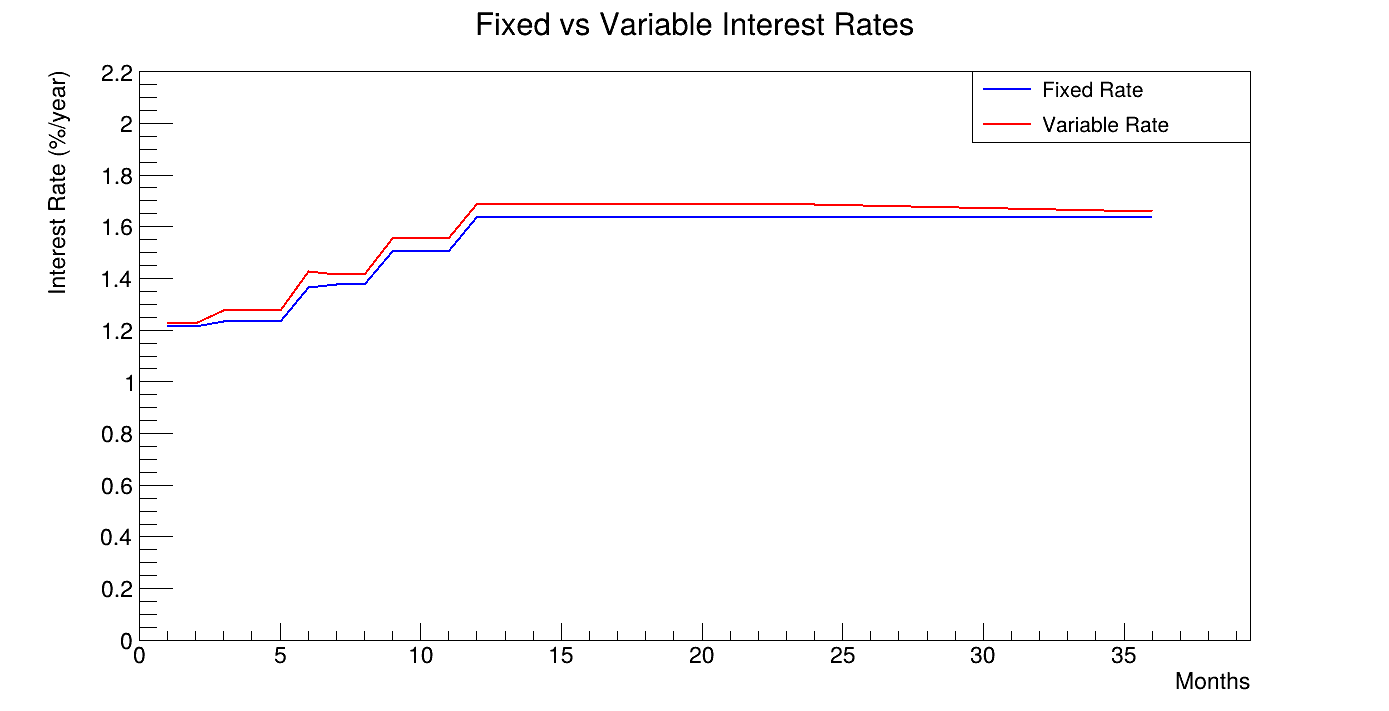

There are two types of CDs: fixed rate and variable rate. They are basically the same most of the time. Fixed rate CDs pay a fixed interest rate for the duration of the CD. Variable rate CDs pay an interest rate that can change, but is higher than the fixed rate at the time. Here is a new tradeoff: do you lock in a fixed rate now, or do you accept a variable rate and hope it does not drop during the CD's term?

For example, the following table shows the interest rate of a Taiwanese bank (TaiShin bank) on TWD at the time of writing.

| Fixed | Variable | ||

| 1 month | 1.215% | 1.225% | |

| 2 months | 1.215% | 1.225% | |

| 3 months | 1.235% | 1.275% | |

| 4 months | 1.235% | 1.275% | |

| 5 months | 1.235% | 1.275% | |

| 6 months | 1.365% | 1.425% | |

| 7 months | 1.375% | 1.415% | |

| 8 months | 1.375% | 1.415% | |

| 9 months | 1.505% | 1.555% | |

| 10 months | 1.505% | 1.555% | |

| 11 months | 1.505% | 1.555% | |

| 12 months | 1.635% | 1.685% | |

| 13 months | 1.635% | 1.685% | |

| 24 months | 1.635% | 1.685% | |

| 36 months | 1.635% | 1.660% |

And the above table in graph form.

CDs are guaranteed by the country's Deposit Insurance company: FDIC in the US and CDIC in Taiwan. Your CD cannot lose its value unless the entire country collapses.

Google "Certificate of Deposit <your bank of choice>" for the exact process of purchasing a CD. This is usually free (the bank actively wants your money to be committed) and usually as simple as "tell the app the amount and duration. The app shows the interest. Click confirm. Money disappears from your account. Wait until the end of the CD. Money shows up again with interest." There will be an option to auto-renew if you want to keep a CD permanently.

On a side note, CD locking is not very strict. If you absolutely need to withdraw your money before the end of the CD, you can usually do so with some penalty. For Taiwanese banks, the penalty is 20% of the accrued interest up to that point and recalculated using the appropriate fixed rate for the actual locked period. For example, if I put 100K TWD in a 12-month CD and I need the money after 8 months, my principal is untouched but the interest I get is 100K * 1.375% * 8/12 * 0.8 = 733.33 TWD.

If I remember correctly, the penalty for breaking a Certificate of Deposit early in the US works differently. The penalty is often three months of interest, flat. You might not get the full principal back if you need to withdraw very early. Consult your bank for details.

Money Market Fund

Money market funds (MMF) are interesting. They provide returns close to or slightly better than mid-term CD rates but never lock your money up. They are investments you can buy and sell at any time. In theory, they are not guaranteed by the government. Historically (even during the 2008 crisis), they have been saved. Some lost value temporarily but recovered, and the fund was backstopped temporarily by the government. In practice, they are treated as being more liquid than CDs, unless you are okay with CD penalties, but they are, in theory, not guaranteed (be careful. This is not a law, but "we cannot let MMF fail or we trigger another crisis").

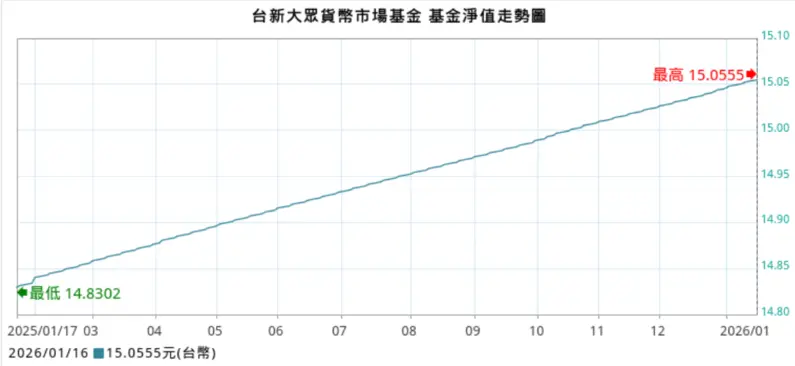

Depending on where you are from, there are two types of MMF: accumulating and distributing. MMFs in the US are all distributing and always have a value per unit of one dollar. Take the famous VMFXX for example. Its price chart is a literal horizontal line. They periodically distribute the interest earned to investors, and the amount is (annualized) basically the government rate.

If you are outside the US (EU, Asia), your local MMF will be of the accumulating type. These do not generate any yield while you are holding them. Instead, their price goes up gradually over time. I grabbed a random MMF from Taiwan. The price of the MMF just goes up a little bit every day, adding up to about 1.55% over a year. This is basically the government rate.

Why consider MMF? They make you more money than just putting your money in a bank account. They are useful when you have some money you know you will need soon but not right now. For example, you just sold your other investments to pay for a new car, but that will not happen for another two weeks. CDs usually have a minimum term of one month. Put that money into an MMF and get a few extra dollars while you wait.

Bonds

This is where real investments start. CDs and MMFs are grouped into a category called cash equivalents. They are not cash in that you cannot pay for anything with them directly, but they are close enough that you can easily get out of them and not lose any money. Starting from here, things are different. You start accepting more volatility on your principal for more total return.

Have you ever borrowed money from a bank or a friend? This is the inverse of that. You are lending your money to someone else, usually a company or the government, at an interest rate and a payment schedule. Broadly speaking, that interest rate is called a coupon rate for historical reasons. Every so often, whether a month, a quarter, a year, or something else, you get paid some amount of interest. Finally, at the maturity date, you get your principal back. This is also why a bond is called debt in the financial market.

Obviously, you might have owed someone money and never repaid your debt. The same risk applies to bonds. If the company or government decides not to pay, your bond is worthless. There will be legal action taken against the company or government to recover your money, but that takes a long time and you will end up with pennies on the dollar. Do not worry, companies and governments do not do this easily, not even close. It is only when they have no option left or are in financial distress that they default. Otherwise, their name (called creditworthiness) gets damaged and future borrowing becomes much more expensive. That is a situation no company or government wants. Their suppliers might also consider the company in trouble and refuse to work with them, causing further problems.

A bond has a fixed face value (for example, $1000 you get back at the end), but its trading price fluctuates every day. When buying a bond, people are always asking, "Do I trust this company to be alive 5, 10, or 20 years from now?" "Do they look like they will be in trouble soon?" "The company asks for $1000, but what if someone else also asks and gives me a better interest rate?" Most bonds are compared against the interest rate of the US government bond. The finance world calls this the "risk free rate" because the US government has a tremendous amount of power, and in theory, they cannot default fiscally. This is a questionable assumption because of politics and other factors, but it is fixed terminology. Why would you lend Microsoft $1000 at 3.5% when you can lend the US government $1000 at 4.5%?

There are many companies that issue bonds. Some are very large, like Apple, Microsoft, Google, Amazon, Facebook, etc. Some are very small, like a local grocery store or a small restaurant. Some are very specialized, like a company that makes solar panels or a company that makes furniture. Some are very risky, where their survival depends on whether their core R&D is successful. Some are not, where they are just moving products around. This makes it difficult to assign a price to bonds. Each bond is unique and has its own risk profile. This is where credit rating agencies come in. They are not perfect. In theory, they should represent the interests of bond purchasers, but they are often influenced by the company and were part of the cause leading to the 2008 crisis. Credit rating agencies assign each company (or government) a credit rating like AAA, AA-, or BBB. The higher the rating, the lower the risk and the lower the interest rate. The finance world puts company bonds into two categories: investment grade or junk. Investment grade (IG) bonds are considered safe and have a high probability of being paid back (remember your entire principal is at risk). Junk bonds are considered risky and have a lower probability of being paid back. Sometimes banks call them high-yield bonds. They are the same. You can risk your principal to chase higher returns, but you might not get your money back. Or you can be safe and invest in an IG or government bond.

If you hold a bond to maturity, you get your principal back (assuming the company is still alive). So, depending on your purpose for the bond, the day-to-day price may not matter. It only matters if you want to sell it before maturity.

So, what makes bond prices move? Besides the company itself, it is the government rate. The government is considered the safest borrower possible. Whether or not that is really the case is debatable, but the market thinks so, and that is all that matters. If the government raises rates, say from 3.5% to 4.5%, suddenly the 4.5% bond from Microsoft is less attractive than the 4.5% government bond. People start selling Microsoft bonds and buying government bonds, pushing Microsoft bonds down.

There is one interesting bond type: the zero interest bond. As the name suggests, these bonds do not pay interest. They are usually issued by governments. Instead of paying interest, they are bought and sold at a discount to their face value. For example, a bond promising $1000 five years later may only be sold for $900. Effective interest is paid at the end of the bond's maturity.

When should you get some bonds? I cannot think of many good reasons, unless you have specific needs (which I do, in a later section). In theory, they provide income so you do not need to sell your other investments if you need extra money. They also, in theory, grow in trading value when the stock market is down. Bonds are a drag on returns if you have the liquidity to survive a crash without selling. I prefer a larger cash/MMF buffer (for survival) and 100% stocks/ETF (for growth), skipping the middle ground of bonds entirely if possible.

Stock

This is what most people associate with investing. Finance 101: stock represents ownership in a company. But that is not what I want to focus on.

Returns from IG bonds are not very high after accounting for inflation. That is fine if you just want more money at the end. But to really make financial goals easier, you need to accept more price volatility for more return. This is where stocks come in. As companies grow and make more money, the price of stocks tends to increase. It can be a lot. Nvidia's stock went up 35 times from pre-AI to early 2026. Robinhood increased fivefold since sometime in 2021.

It is very tempting to try to find the next Nvidia and buy before it goes up. If you can do that consistently, it will make you rich. However, due to a principle called the efficient market hypothesis, it is virtually impossible to predict where a stock or the entire market will go. The only thing we know is that historically, markets tend to go up on average, with downturns in between.

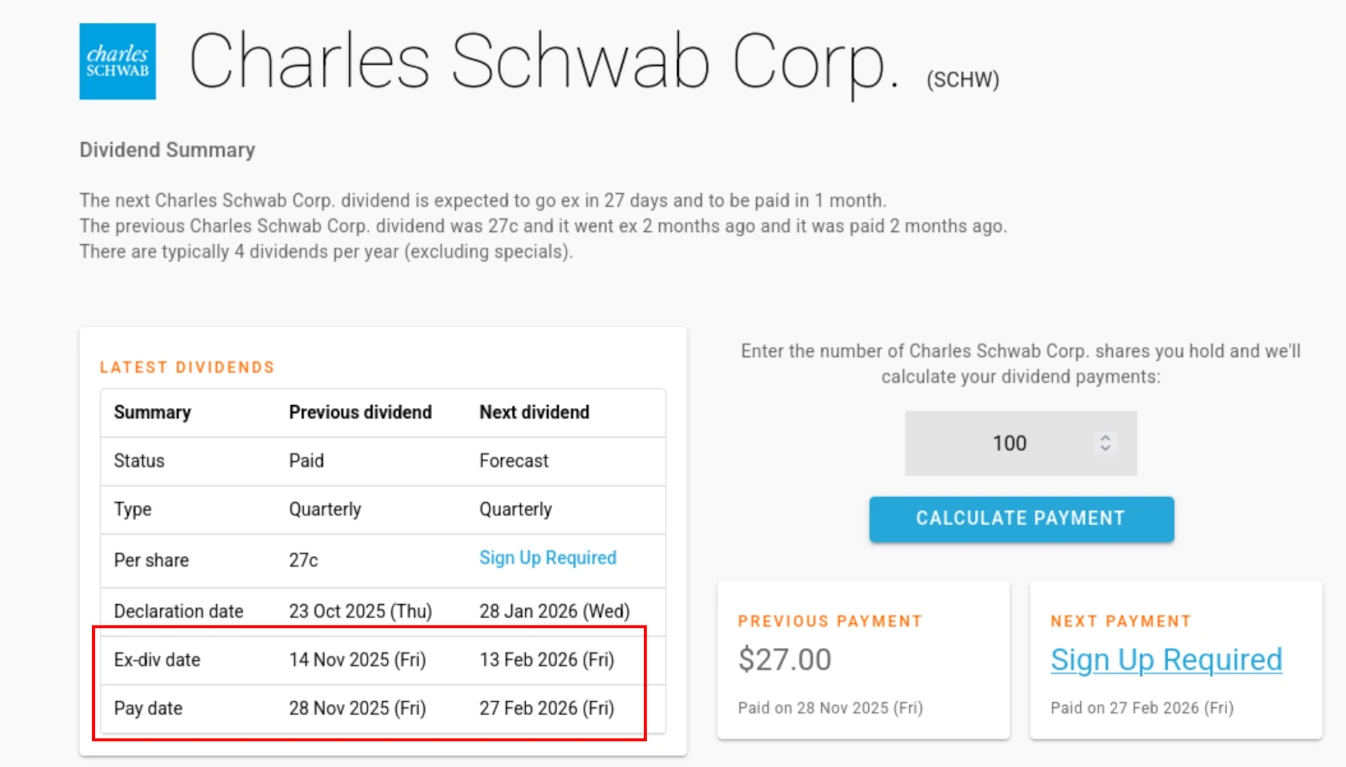

Some stocks pay dividends. This is a small amount of money paid out by the company to its shareholders, usually a fixed amount per share. Who receives the money is decided on the ex-dividend date. If you hold the stock on the ex-dividend date, you get the dividend, even if you sell the stock afterward. Later, the dividend is distributed on the record date. Because dividends are basically the company saying, "We have no idea what to use our cash for, so we will just pay our shareholders," stock prices immediately drop by the amount of the dividend on the ex-dividend date.

Some investors care a lot about dividends. Dividends exist, which is why I mention them. But my view is that it is your money paid back to you. It is like being forced to sell a fraction of your shares every so often. It reduces compounding, and you really should just sell shares if you need money instead of waiting for the dividend.

(Mutual) Funds

Stocks are great. They can have high returns. Or the company behind the stock could fail and your stock becomes worthless. But it is often impractical for people to buy enough stocks that the failed ones do not matter. That is where funds come in. Funds are groups of people pooling their money together, agreeing on a common investment strategy, and buying more shares together. Each person owns a fraction of the fund based on how much they invested. That strategy could be as simple as "buy stocks so that the ratio of dollars invested to the market cap of the company is the same for all stocks," called a market cap weighted index fund. Or it could be as complex as "Tom here is a legendary investor who has been investing for decades and has a track record of beating the market. We will hire him for a fee of 1% of the fund's total assets and let him decide what to buy and sell." (This is usually a bad idea, but banks love to sell these funds because they are profitable for the banks.)

Unlike stocks, funds are managed by a fund manager (the person doing the buying and selling of shares). They are usually paid a fee for their services, which is a fraction of the fund's total assets. This fee is called the expense ratio. You do not pay the expense ratio directly. Instead, it is deducted from the fund's total assets. If a fund has an expense ratio of 1%, then one year from now, all things being equal, the fund would lose 1% of its value.

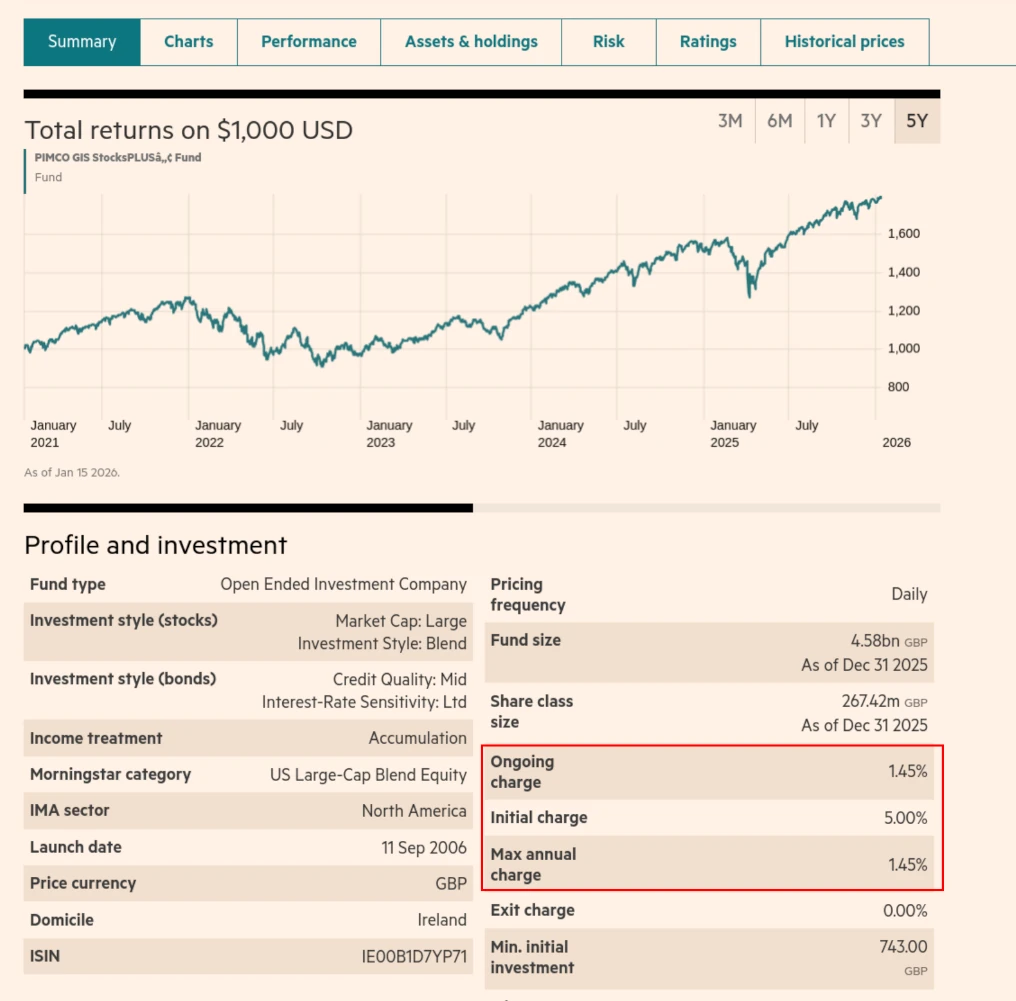

However, not all funds are equal. Some poorly designed funds will charge you an initial 5% and then 1.45% ongoing just because you own it, and then underperform a cheap fund (not this one; underperforming funds get deleted and become unsearchable). Avoid funds with high expense ratios.

Famously, Warren Buffett himself bet one million dollars against hedge funds (which are basically very expensive funds) that they cannot win on average against simple market weighted indexes. Buffett won by a large margin.

Funds can invest in assets besides stocks. For example, bond funds invest in bonds. Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs) invest in real estate. Technically, money market funds are a type of fund, but in practice, they are treated very differently, as MMFs internally hold ultra short-term bonds instead of various stocks.

Market cap weighted ETF

This is what I hope most people are investing in. Traditionally, you cannot buy funds on a stock market. They are "stock" markets. Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) are still funds, but the finance world has retrofitted them to be traded on stock markets. Market cap weighted just means if Nvidia is 10% of the market cap of some index (say S&P 500), then Nvidia will be 10% of the ETF's total assets. This strategy is simple, and simplicity is important. As the fund managers buy and sell less frequently, they have lower transaction, regulatory, and operational costs, leading to a lower expense ratio. The SPY ETF is the most famous market cap weighted ETF and only has an expense ratio of 0.09% (compared to 0.15% for DFEOX and 1.45% for the PIMCO StocksPLUS Fund). Other ETFs that track the S&P 500 have an even lower expense ratio, like the Vanguard S&P 500 ETF (VOO). It is the exact same thing, but only costs 0.03% per year.

Remember, the expense ratio is the percentage of money you lose every year automatically. For the exact same thing, the lower the better.

Target date funds

I do not agree with these funds, but they do exist and have at least a coherent purpose (funds are a very broad category). The standard investment advice is for young people to invest everything in equities (stocks or stock ETFs), then gradually move to bonds as they age to reduce the risk of a stock market downturn affecting their retirement. Bonds have a fixed payout, and the trading price of a bond is more stable than stocks. Target date funds automatically adjust their allocation to stocks and bonds as the target date approaches, so that on the target date, the investor can start selling their share of the fund to fund their retirement. See the following graph I borrowed from Vanguard.

However, due to the nature of a target date fund, their expense ratio is higher than a market cap weighted ETF. The fund manager must gradually sell off equities to buy bonds. Some poorly designed funds would ask for 0.75% or even 1% per year, while some (like those by Vanguard) are at 0.055%. Though still higher than their VOO ETF at 0.03%, this is pretty good across the market. Target date funds are useful if you do not have the time or interest to manage your own investments. They can be a fire-and-forget solution. Sometimes, the time saved might generate more income than the expense ratio.

UCITS

This is something only non-Americans (officially NRAs, non-resident aliens) have access to. I said I would not touch on tax, but there is one aspect that is very important. The US, by default (assuming your country of origin does not have a tax treaty with the US), takes a 30% tax on your dividends. This is called the withholding tax. UCITS (Undertakings for Collective Investment in Transferable Securities) acts as a workaround for foreign investors. Instead of paying the withholding tax, UCITS funds/ETFs put their fund in a European country that has a tax treaty with the US, reducing the tax on dividends down to 15%. For legal reasons, most (but not all) UCITS assets are of the accumulating type. When the fund receives dividends, they automatically reinvest the dividends into the fund instead of distributing them to investors.

UCITS usually have a higher expense ratio than their US ETF counterparts, but this is a rare case where the higher expense ratio is worth it. Take the US-based IVV (iShares Core S&P 500 ETF) and the European version CSPX (iShares Core S&P 500 UCITS Acc ETF). S&P 500 ETFs generally have a dividend yield of around 1.05% per year. If you hold the US version, the real cost is 0.03% (expense ratio) + 1.05% (dividend yield) * 0.3 (withholding tax) = 0.345%. With the UCITS version, the real cost is 0.07% (expense ratio) + 1.05% (dividend yield) * 0.15 (withholding tax) = 0.2275%. This is about one-third cheaper overall.

| IVV | CSPX | ||

| Exp Ratio | 0.03% | 0.07% | |

| Dividend | 1.05% | 0.00% | |

| US wit tax | 30% | 15% | |

| Real Cost | 0.345% | 0.2275% |

For the same reason, NRA investors SHOULD NOT (in the RFC 2119 sense) buy US-based MMFs. You immediately pay 30% on the yield. Use your broker's idle cash rate (good brokers give you slightly less than the MMF rate), buy ultra short government debt (highly liquid and risk free). Both options are US tax free for NRAs. Or use UCITS MMFs; paying 15% on yield is a lot, but still better than 30%.

The US also has a very harsh estate tax for NRAs. If you die with US assets, assets above USD 60K are taxed at 40%. This is a huge tax. Europe generally, including UCITS, does not have this problem. Your spouse or child gets your stocks free of US tax (but your country's estate tax still applies).

Not all brokers offer UCITS funds/ETFs, as they are not listed on US exchanges. Most often, they are on the London Stock Exchange (LSE) or Frankfurt Stock Exchange (XETRA). You will need to check if your broker provides access to them. The safest route is to go through Interactive Brokers. Schwab provides limited (and expensive) access to UCITS.

Also note that, unlike US investors, the Taiwan government does not impose any sort of capital gains tax at all (there is an Alternative Minimum Tax in Taiwan applied to profits from foreign investments, but the base is so high that encountering it is a good problem to have). Your local regulations may vary. It is important to understand that most online advice assumes you are a US citizen. Understand the assumptions and adapt them to your situation.

Traps

The above are the instruments you use to construct your portfolio. I have alluded to some of the hidden traps in the previous section. Here, I want to go deeper into them and show how they can creep up.

Bank fees

Banks are very expensive. I do not mean that putting your money in a bank account has a tremendous opportunity cost. No. Banks charge (in my opinion, unreasonable) fees everywhere. Sending money from my Taiwan account to my US-based broker? USD $30. Need some physical EUR cash for travel? USD $45. Want to hold bonds at the bank? 0.5% of the face value. Sending a bit of money to your friend because you are buying something from him? That is USD $0.5.

Put your investments in a broker, never at a bank.

Fortunately, banks publish their fees on their website. They have to. Give it a read if you have not already. You will often find where your money is disappearing. As banks already hold your money, the fees are truly hidden. They just disappear from your account instead of being shown as paid explicitly.

Expense ratio

The expense ratio is an amount paid to the instrument itself. Some funds have a high expense ratio. Please read the fact sheet of what you are investing in before spending the money, and do not invest in funds with high expense ratios, as they eat into your investment returns. Think of it this way: the real benchmark is not "will this investment lose money," but "can the $1000 be invested elsewhere to be more productive than the investment being considered."

Once I was setting up wiring to a new account so visiting a physical branch (Taiwan laws). A bank employee shows up and pitched a fund that costs 3% per year. After a long, wordy and convoluted explanation on why I should invest in the fund, I essentially asked "so you are claiming that the fund beats its benchmark at least 3% a year without taking on significantly more volatility?" The long story short was no. In order for the fund to catch up with the 3% expense ratio, they are using leverage which inherently increases the risk of the fund.

The real return

It is not enough for an investment to just not lose money. Investments lock your money up, make it unusable until a future date, be it predefined or when you sold the investments. The real return is the return after taking into account inflation during the lockup period. From a purely consumption point of view, if inflation is 6% but your investment is returning 4% per year, after a year you would expect what you can buy by selling the investments to increase by 4% - 6% = -2%. You are better off selling the investment and spending the money.

Yes, the real world is not as simple and there are many reasons to keep the investment despite losing to inflation (called losing purchasing power). Sometimes you have to accept negative real returns in order to guarantee the principal is always available. This is sometimes true for Certificates of Deposit.

Asset allocation

Here is where I justify my own decisions. Yours will vary. We all have a different problem to solve. For me, my stated goals and constraints are:

- My job is unstable. Not gig work unstable, but startup implodes and startup availability is highly correlated with US tech sector and thus the stock market.

- I earn USD but I spend in TWD and EUR mostly. I get screwed if USD suddenly weakens while I do not have a job.

- During my jobless period, I still wish to go to FOSDEM and CCC and purchase equipment to maintain my career. They are important career events. My financials failing to enable so is a failure of my planning.

- I still wish to have the option to retire at some point.

Here is the problem. I work in tech startups. These are unstable jobs. I can count on the fact that I will be unemployed at some point in the future despite my best efforts to not be, just I do not know when. I must not starve and I wish to continue traveling and purchasing equipment. Servers and SBCs for development. That is a fairly difficult demand to satisfy.

Most traditional advice treats human capital (your capacity to work and generate income) like a bond. It looks close enough if you squint really hard. You work, which does not matter for the finance world, and you bring in new cash every month just like a bond paying monthly. You are lucky if that is the case for you. For me, I work in the world of startups, and startups can fail unexpectedly. Thus, my "human capital" acts more like a stock. Sometimes I have time, other times I do not. It is a fact I have to work around.

Again, the obvious solution is to put what I expect to spend during unemployment, plus some extra buffer in a bank account and never look at it until I need to. If 2008 ever happens again, however, I expect at most 2 year unemployment period. So let us plan for 3 years just to be safe. 3 years is an exceptionally long buffer that I decided for myself. It is on the very long side but ultimately I cannot predict what VCs will do during a downturn. I should not go out of work for a year. really no reason for 2 years and anywhere beyond that I need to pivot. If you are working a normal corporate job, you do not need that much, maybe 1.5 years at most, I guess. And understand the buffer will definitely eat into your eventual net worth as it is not compounding at the market rate.

If I just held cash, I lose about 2% per year to inflation. That is a lot of money over time. As I do not know when I will need the money, it is difficult to piece together an investment plan that guarantees the money to be available when that time comes.

Cannot be done with stocks. A recession might happen and I lose 50% of the value when I am most likely to be unemployed. Not even with bonds. If I purchase a short-term bond, I lose to inflation. If I purchase a long-term (say 30 years bond) and the government raises interest rate, my bond loses in trading value nor can I pay my bills on the face value. Plus what if TWD rises in value? My saved USD now exchanges less than it did before. That is also a major problem.

So let us not. I will accept some loss to inflation. I want that loss to be as small as it can be as long as minimizing it does not violate my need for cash when I do. Looking into my problem more carefully, I am pretty sure I will need the 1st year of money. Second year not so much and the third is really a backup, just in case. Nor do I expect I will need the second and third year money when the first year begins. Let us structure around that.

Let us use some numbers to make the discussion easier. Say I expect to spend (of course the real numbers differ, to protect my privacy):

- TWD $300K

- EUR $2600

- USD $1400

...each year. 3 years it is TWD $0.9M, EUR $7800, USD $4200.

(Currency) risk management

Given that I spend in three currencies and I do not wish to speculate on FX, the most effective way to ensure I do not deplete a specific reserve is to diversify my savings across these currencies. Instead of holding all my cash in TWD or EUR, I allocate the amount I expect to spend in each currency into separate accounts. Holding assets in the currency of spending is the only free lunch in hedging. This approach ensures I have sufficient funds to cover my expenses in each currency without worrying about fluctuations in exchange rates.

Given I know I spend Euros end of year for CCC and FOSDEM and knowing I need them each year, instead of putting them into an MMF, it is more optimal to store the Euros in short term European bonds that mature before end of January (after CCC, when credit card bills land). Short (1 year) bonds mature often enough that I expect I am more than likely to not need to sell the bonds before maturity. Plus they are less sensitive to interest rate changes so I most likely will not be selling at a loss.

For USD, the situation is a bit more tricky. Unlike Euros used for traveling, I do not know exactly when I spend them. I might need it tomorrow for a new SBC that I will be reverse engineering. Or maybe never in the planned 3 years. There is no perfect solution. The solution I end up with is that: Put a tiny portion in UCITS Treuries MMF like IB01 (which does not pay the witholding tax because they use treuries inseted of IG bonds!). This covers the immediate need for USD. Then the rest in a short, 1 year US bond. This is tax free and earns me the full risk free rate. Accepting that if I ever need the money early, I might take a loss.

And about 200 lines of Python automates that rolling on Interactive Brokers.

For TWD, that is more a steady expense and a lump here and there. I will just put that in a Certificate of Deposit maturing every year. Taiwanese bonds are terrible to deal with and MMFs have a lower yield than CDs at the 1 year term.

Liquidity laddering

But I can do better for my TWD needs. Keeping all 3 years of expected expenses in a large 1 year CD is not efficient at all. I still incur a penalty if I suddenly become unemployed as I need to break the CD for living expenses. To solve that we need CD ladders. Instead of putting all TWD 0.9M in a single CD, I split the 0.9M into 12 smaller CDs maturing every month and automatically roll them over to a new CD when they do mature. This way I just need to stop the automatic rollover when I need the money. As Taiwanese CDs do not meaningfully increase in interest after a year, it is not worth the hassle to set up 24 and 36 month CDs. It is much simpler to have 12 of them and at the end of month, roll what I have not spent into a new CD maturing next year.

Setting this up is a painful process but it only needs to happen once. When I decide this is what I want to do, I create 12 new CDs maturing 1 to 11 months with no automatic rollover and a 12 month CD with automatic rollover. Helpfully each month the bank app will notify you about the CD maturing as the bank deposits it into account. This way I am reminded to create a new 12 month CD with automatic rollover enabled. Completing the ladder a year later.

However, CDs even at the 1 year term do not cover inflation. I actively need to add more money to maintain purchasing power. Yet adding more money into CDs is a pain (cannot use automatic rollover). Such continuous administration is a hassle I do not wish to deal with. Solution: have a TWD MMF on the side that I can add to every year. This also doubles as my emergency fund. If I ever run into trouble and need quick cash, I pull from here. And add 2% (beyond the CD's 1.6%, so more than inflation) of the CD value to the MMF every year to maintain purchasing power. Likewise, adding a tiny bit to EUR/USD bonds is impossible. Even though breaking perfect neutral hedging, I opted to just add to this TWD emergency fund to maintain purchasing power there as I feel I am at the utmost complexity I could manage comfortably.

Side note: Despite the pain of setting up CD ladders and only 0.2% difference in yield, putting everything in TWD MMF will not work as expected. In Taiwan you will likely hold your funds in a bank provided trust (legal reasons). This trust adds another 0.1 to 0.2% drag on the yield (making the final yield just 1.2%! Worse than 1 month CD rate). Nor are TWD bonds available to individuals. Making both non-options as the main instrument.

The TWD $900k CDs also act as a important part of unlocking VIP services at Taiwan banks (most asks TWD $3M in funds, deposits or insurence. Stocks and ETF does not count). In return gives me reduced spread converting my US salary to TWD living expenses among other useful discounts.

Opportunity cost calculation

Let us check the opportunity cost of the CDs and bonds are not too high by benchmarking against the dead simple alternative of 100% SPY. The proposed CD and bond have the initial value of USD $43200. Assuming a 1.6% yield on TWD, Germany EUR bonds at 2.3% and US 1 year government bonds at 3.6%, the total yield per year comes out to USD $838.2. While the SPY returns on average 8% per year, so $3456.0. Leading to an opportunity cost of $2617.8. This is effectively the insurance premium against my own job loss and startup uncertainty.

That is a lot of money. But ultimately acceptable if it means I get to survive the next 2008 without stress and anxiety.

Failure conditions

The above plan assumes several things that are not always true. Which I need to be aware of and handle accordingly (not panic).

- My main assets are the 0.9M TWD CDs. They pay a miserable 1.6% per year. If Taiwan ever enters a high inflation period, my living expenses go up. Then I either have to cut back my spending or put more money into the CD.

- If I fail to find a job within 3 years, my career strategy failed me. I do not have a backup plan. I must pivot before so or start selling my equity (see the next section).

- If the bank I put my CD in goes bankrupt, they are protected by the Taiwan CDIC (up to 3M TWD). But it might take me some time to make them liquid again.

Honestly, I feel the only real threat is the first one. Which is acceptable as there is no solution around it (Taiwan does not make inflation protected bonds (or bonds generally) accessible, and they eat into the yield anyway, defeating my goal to minimize cash drag during normal inflationary periods).

There is also a sneaky risk: the opportunity cost risk. Where my 3 year buffer is too large, causing me to miss out market returns and causing my retirement to fail. However, I know my own income and decided that is no issue.

And some critical assumptions about the infrastructure I am working with:

- Rolling CDs are free (been true forever in Taiwan).

- Rolling bonds are cheap (true on good brokers like Interactive Brokers).

- Moving money from broker to bank for spending is cheap (this needs work. Interactive Brokers gives you a free withdrawal each month. And with AUM (aka the CDs and some asset parking) you can get Taiwanese banks to waive fees on accepting incoming international transfers. Or if you are using HSBC, use their GVGT feature).

- I can directly spend USD/EUR despite using a Taiwanese bank (only a few banks provide this feature).

Long term investment

That sorts out the "do not starve and be alive" part of finance. How about retirement? I cannot be trying to retire on a savings account. Not planning to do so. However let us review the most common strategy: Buy SPY and never look at it until you retire. While that worked in the past 30, 40 years, it has one glaring problem: It assumes the United States will continue to be the world's largest economy and grow at the rate it does now. I do not know about you, but feels like a shaky assumption to bet my retirement on. Again this is not investment advice but "why I choose what I did."

If you break investing down, it is really just making many, many positive expected-value bets. The chance and penalty when your bets fail is then the risk you are taking on. Sometimes the bets are explicit, like buying NVDA. Long term you are betting that Nvidia will go up, comparing to the price of today. Some are implicit. By buying SPY, even though you bought the top US companies, you are still betting that the US will not enter a long term recession.

For me, the solution comes from diversifying some of my bets to the entire world, so unless WWIII happened, which I am screwed anyway. By doing so I accept my expected return would be slightly lower than recent S&P 500 averages. The US has been growing at a weird rate compared to the rest of the world. Usually the solution comes in the form of VT (Vanguard Total World Stock Index Fund ETF), but since I am an NRA so the VWRA (Vanguard FTSE All-World UCITS (USD) Accumulating ETF) is the better choice. Beyond so, I actually choose AVGC (Avantis Global Equity UCITS ETF USD Acc ETF). Not going to explain the exact reason, but (academically) Avantis ETFs have a higher expected return than simple index funds while maintaining low expense ratios.

I do not plan on touching the long term portion of investment until I retire. Or I fail to find a new job within 3 years, this will be my last resort.

Choosing your bank

Traditional banks are really expensive. You should use fintech companies like Wise or Revolut (depending on where your paycheck is sent from) to make moving money from work to broker cheaper. And that should be the majority of where your money goes. However, I still need to interact with banks for a local credit card, paying bills in TWD, and avoiding the 2% international transaction fee on local spending from fintech. In other words, banks are unavoidable. Here is how I select one.

Cost

At least for Taiwanese banks, there is no account maintenance fee (you can leave the account at $0 and they will not charge you), minimal national wire fee, and minimal-to-no ATM fee (at most NTD $5, approximately $0.15). However, anything beyond the basics costs money. Read the brochure carefully before opening an account. If you have extra funds, consider the bank's lowest-level wealth management/VIP plan. Taiwanese banks do not charge maintenance fees based on AUM. Instead, they assign you a Relationship Manager who is essentially a salesperson, and you can respectfully ignore their pitches. Some banks, like Fubon or SinoPac, often provide reduced FX spreads and waivers for incoming international wire transfers. And a free safe in you ever need one. These benefits could easily add up to a few hundred US dollars per year and actually being useful on your cirtical path.

However DO NOT follow the bank's product advice. They sell you garbage high fee products that frankly are easy and much cheaper to replicate in a real broker.

Also consider FX spread as part of your cost calculation. Banks usually follow the spread published by Bank of Taiwan (yes, they have retail banking). The spread is typically 0.05 TWD/USD during work hours, or around 0.16% depending on USD strength at the time of calculation. Some banks offer an across-the-board discount to 0.04 TWD/USD for all clients. Others do not offer a general discount but can reduce the spread to 0.02 TWD/USD for clients with the lowest tier VIP status.

Credit and Credit Cards

Credit in Taiwan works slightly differently than in the US or Canada. Personal lines of credit are very rare, and using one actively hurts your credit report within Taiwan. This is mostly a systemic shock after the 2005 "cash card" disaster. Unlike credit cards, these cards allowed users to borrow real cash from ATMs at high interest rates. With prominent advertising, people abused them and then defaulted on their loans. Now Taiwanese banks refuse to lend out credit without checking what you are doing with it.

However, credit cards are still readily available and very useful. You should never, ever put a balance on your credit card or spend beyond your means (luckily Taiwanese banks hate balances on cards). I spend across 3 currencies, and frankly, sometimes I just do not know how much of each currency I will spend each month. There is a pattern, but it is difficult to maintain reserves of each currency because things always pop up. New hardware to purchase, experiments I am running that cost me an extra 100 bucks.

Some Taiwanese banks provide dual or multi-currency credit cards, usually branded as business cards - namely E.Sun Bank, TaiShin, MegaBank and CTBC (KGI has one but is hot garbage). Unlike normal cards, where if you spend anything not in TWD, VISA/Mastercard will exchange the amount into TWD and you are billed in TWD, the dual/multi-currency cards will not do so. Instead, on a USD card, all non-TWD transactions will be billed in USD. The same applies for EUR. This is a godsend for me since I earn USD. I can avoid conversion to TWD just because I live in Taiwan, while the spending is in USD. Likewise for EUR, I do not earn Euros, but being billed in Euros allows me some control over the exchange rate and makes the EUR side of currency hedging possible in the first place.

Due to Europe's cap on interchange fees, credit card rewards are often limited or unavailable when spending happens in the Eurozone. The dual-currency cards generally do not have these limitations (which is kind of the point).

Also, keep a small buffer of USD and EUR on the side. These multi-currency cards will try to pay from your foreign currency balance first. If that fails, the bank only converts the minimum payment from TWD and pays that automatically. Though again, Taiwanese banks hate this and will do everything they can to notify you about the carried balance.

Never spend what you don't need.

Note that not all multi currency cards are credit cards. Namely the HSBC and DBS cards are debit. They will automatically convert your TWD savings into the spending currency at the bank's announced exchange rate before any discounts. Which one, has no option to convert USD and two, is likely to be more expensive than Visa or Mastercard's rate if unlucky.

Sending money internationally

You really should not let the majority of your salary touch the local banking system. Wise and/or Revolut is much cheaper. However in the event that you do need to or your cashflow pattern forces you to, consider the cost of sending an international wire. Banks will use SWIFT to send money internationally. Cost is about USD 20 to 30 per transaction. There are 3 banks that give you some free options, each with their own pros and cons.

DBS is the cleanest one. Despite what online resources say, DBS Remit in Taiwan allows you to send foreign currency to the currency's home country for any purpose absolutely free of any charge as of writing. However DBS is basically an Asian bank, so there is no option for opening a European or North American bank account with them.

HSBC is everywhere, including the US and EU. Unlike DBS they do not have free money wires to everywhere. But they allow free transfers across your HSBC account across countries. They are the only working option if you need a local bank plus a NA/EU bank account. However, HSBC is a pain to work with and terrible, terrible fees.

Standard Chartered is available in the EU. They are more pleasant to work with than HSBC with better fees. But they do not allow you opening an NA account. Same free transfer options across your Standard Chartered account between countries.

TL:

- Location: HSBC > Standard Chartered > DBS

- Fee: HSBC >> Standard Chartered > DBS

- Transfer options: DBS > HSBC > Standard Chartered

Consider your usage pattern, try to get Wise or other Fintech working and only consider banks to handle transfers if you have to.

High Yield Savings Account

High Yield Savings Accounts (HYSA) barely exist in Taiwan. There are some options available, but they are generally poor choices - either with extremely low caps on the high-yield portion or high barriers to earn the full interest rate. You are safe to ignore them, and the money should be in your broker account, invested.

Instead, for cash buffers you need to keep in the bank, put your money into a 1-month CD. Wait for it to mature, take what you need, and repeat. At least that way you earn around 1.22% interest consistently.

Digital banks

Digital banks are approximately the Taiwanese equivalent of what fintech is to the US. They usually act as a front end for traditional banks, allowing you to deposit, withdraw, transfer, exchange, and invest like you would through traditional banks. They have a nice app UI/UX and often offer nice discounts without any AUM or commitment requirements. However, they come with their own downsides too. Digital banks, without you going to one of their affiliated branches, will only provide a very limited daily withdrawal limit due to regulation. They have none or very limited credit card selections (often co-branded with their backing bank and does not offer the multi-currency cards I need). Have extremely low limits for high-yield savings.

Almost always the est tier of wealth management/VIP at any traditional bank will give you much better, useful discounts and rewards. Also whether deposits or assets held in digital banks count towards VIP status at the backing traditional bank is up to each and more often then not, not. They are useless for my purpose.